What's the point of Burgmüller's 'Candour'?

- Steve Armstrong

Join the mailing list

Get the latest updates on new courses and blog posts

Below are three excerpts from three different editions of Burgmüller's 25 Easy and Progressive Studies, op. 100, no. 1 'Candour'. Spot the difference!

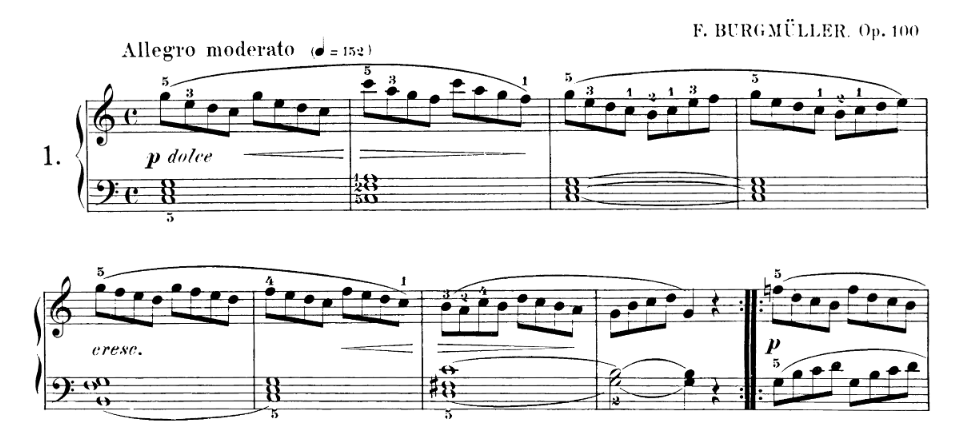

Excerpt A

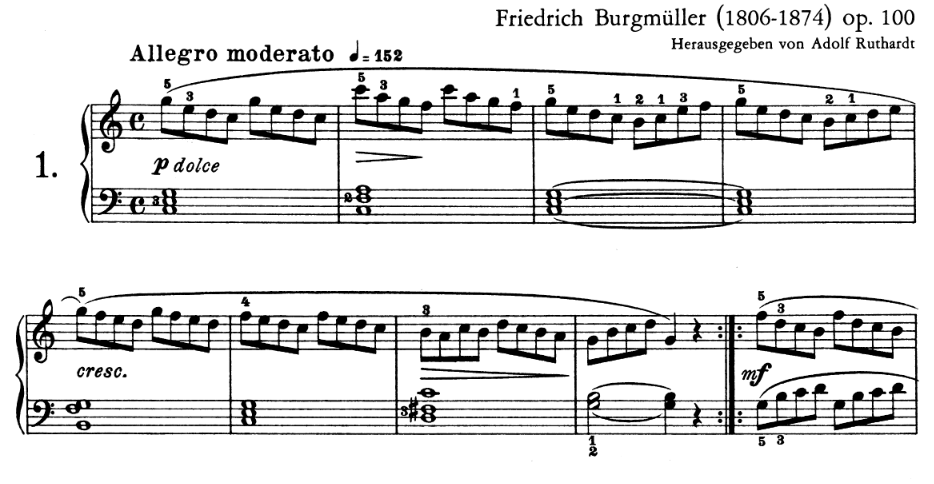

Excerpt B

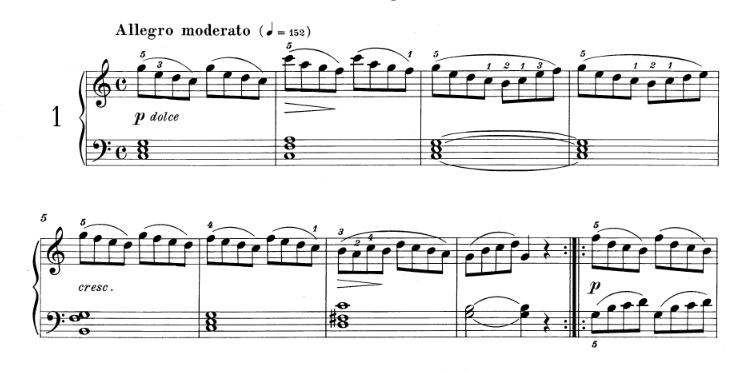

Excerpt C

There are some differences between the dynamic markings, but most significantly—and probably most obviously—are the differences between the slurs. In Excerpt A (Schirmer, 1903, Oesterle, Ed.), there are four slurs equally dividing the opening eight bars; in Excerpt B (Peters, 1903, Ruthardt, Ed.), there are only two slurs; and in Excerpt C (Wiener, 1990, Taneda, Ed.), there are 12(!) slurs. Do you know which is the most authentic and does it matter? The answer is Excerpt C and, yes, it absolutely matters. Excerpts A and B are not necessarily "wrong"; they simply show different interpretations of phrasing and—I would suggest—imply detachment between the slurs. However, the slurs in Excerpt A are not phrase slurs, but articulation markings.

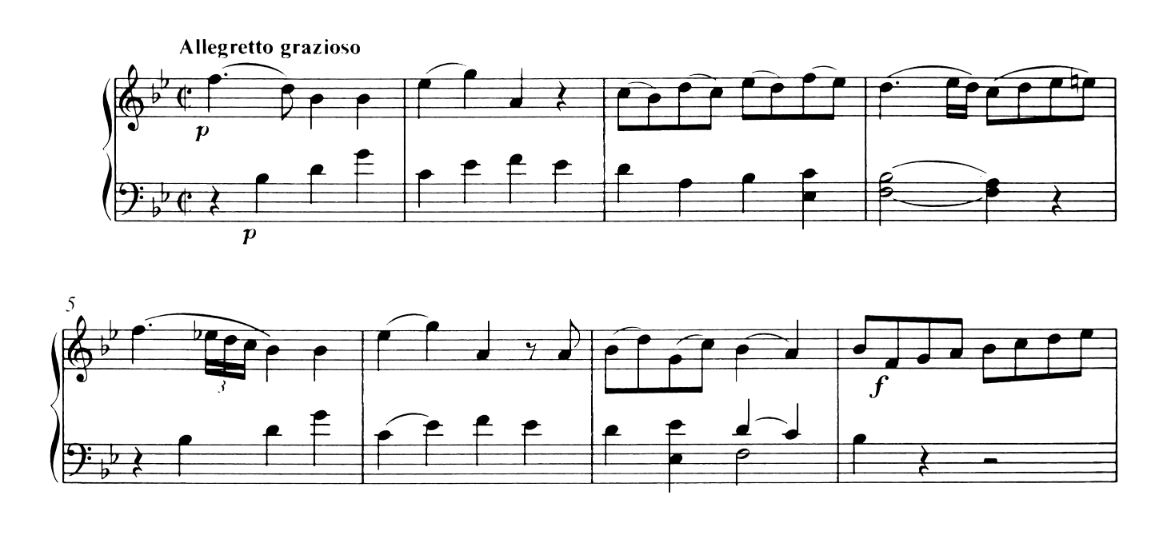

Now the question is whether we detach each slur. It is generally accepted in the historical performance practice literature that a succession of short slurs implies detachment only when the notes are slurred in pairs, as in bar 3 in the following excerpt from Mozart's Piano Sonata no. 17 in B-flat major, K. 570, iii (1789, Máriássy, Ed.).

Daniel Türk and Carl Czerny argued that successive short slurs over several notes shouldn't be detached from one another, Czerny adding that detachment occurs only when indicated by a dot or dash on the last note. However, Johanne Brahms argued that the choice to shorten the last note—thereby detaching the group—is a freedom and refinement in performance.

We have to remember that the marking of short slurs has its origins in string music. A short slur indicated that the encompassed group notes were to be taken in one bow. Unless clear detachment is desired, the effect of changing the bowing direction is comparatively smoother than completely releasing a key on the piano. Additionally, it lends itself to an imperceptible accent—as Leopold Mozart put it in his treatise on violin playing—on the first note of the slur followed by a diminuendo.

Another consideration is that composers often used short slurs merely to draw attention to significant structural details, especially motifs, which could be the case in Candour as the motif appears in almost every bar, transposed, inverted, or transformed. Still, some composers felt that the accent-diminuendo was not implied. For example, Mendelssohn considered such an interpretation to be customary only in the Baroque era.

So, if we are to make a choice, it should be an informed choice and we need to take into account the character of the piece. The tempo description (allegro moderato), the meter (simple quadruple), a prevailing rhythmic pattern of quavers, and a slow harmonic rhythm suggest a fairly fast tempo; but the suggested metronome marking of 152 is—in my opinion—much too fast to the detriment of the character which is explicitly defined as dolce—sweetly. I think a tempo range of 116-138 is more appropriate.

What impact, then, would detaching the slurs have at this tempo? The constant detachment is a disruptive element like some kind of musical hiccup. I hope you’ll agree that maintaining legato better conveys the character.

If we use editions such as from where Excerpts A and B are taken, we limit the expressive possibilities because there are no short slurs; we miss the technical implications of the short slur, too, i.e. the dropping of arm-weight on the first note and lifting the wrist forward through the slur. The technical and musical execution of the short slur is, after all, the primary pedagogical purpose of this study, evidenced not only by the ubiquity of the short slur but also by the logically sequenced second study, Arabesque, that addresses the same fundamental concept but with detachment as indicated by the staccato marking at the end of the slurs and the rests between them.

Performed by yours truly:

About Steve Armstrong

MEd (ECU) | GradCertEdDes (MON) | GradCertEd (ECU) | BMus (hons)

Steve founded a brick-and-mortar music school, Advantage Music Academy in 2018 in Perth, Western Australia, where he leads a team of 10 teachers, including piano, violin, guitar and voice teachers. In 2023, the Academy reached a student body of 300, which includes one-to-one instrumental lessons and an original early-years program, Early Starters Music and Movement and Head Start Piano, which has been featured on the Integrated Music Teaching podcast.

Steve has over 20 years of teaching experience in the studio and the tertiary sector, in which he was a multi-award-winning lecturer of musicology. He holds a bachelor's degree in classical piano with first-class honours (UWA), two postgraduate graduate degrees in educational leadership (ECU) and one in educational design (MON).

Steve's reputation for excellence and leadership in pedagogy led to an invitation to join the Australian Music Examination Board as a piano examiner in 2023.

His passion is mentoring teachers in the application of education research and practice to maximise student learning outcomes and mentoring studio owners, particularly in the areas of recruitment and policy.